By Mirette Magdy

(Bloomberg) — Egypt is in the throes of a familiar crisis;

the currency has plunged, foreign-exchange is in short supply

and living costs have soared. It’s a once-a-decade experience

that’s made the country the International Monetary Fund’s

second-biggest borrower after Argentina.

Policymakers say this time is different, and a swathe of

promised reforms stand to give a makeover to Egypt’s markets,

economy and perhaps society as a whole. But that hasn’t made it

much easier to predict when the current crunch may end.

Here are five areas to watch that may show where things are

heading next.

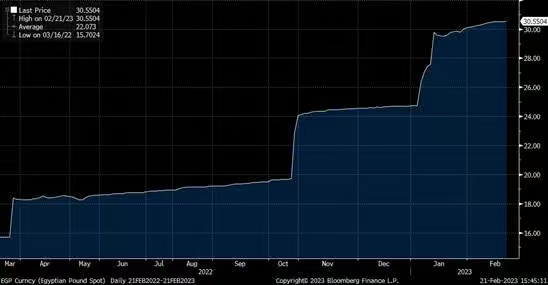

The Pound

In compliance with a longstanding IMF demand that helped

secure a $3 billion deal, the Egyptian currency is more

flexible. But long stretches of stability have followed bursts

of volatility and steep downswings.

Ending that uncertainty, and showing the practice of using

international reserves and banks’ foreign assets to protect the

pound has been truly cast aside, may be key to almost everything

else. Investors won’t pour more money into bonds or company

stakes if they can’t rule out another plunge in the currency.

Some more modest dips and climbs for the pound in the weeks

ahead would be a sign it’s more accurately reflecting supply and

demand. The steady resumption of some imports after the clearing

of a backlog at Egypt’s ports would also show foreign-exchange

flows are improving and pressure on the pound easing. But while

the steepest falls may be over, analysts including at Standard

Chartered Plc and HSBC Holdings Plc aren’t ruling out more

weakening this year.

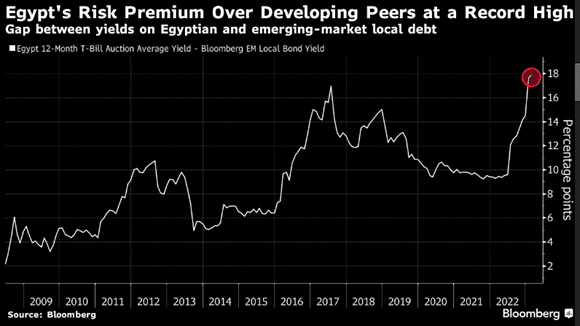

Debt

The days when foreign investors held over $30 billion in

Egyptian local debt may be long gone, but a modest revival in

overseas interest before July will signal the country is on

track to cover its immediate funding gap.

Authorities are targeting $2 billion in net inflows by

then, a goal that likely depends on investors’ confidence the

pound isn’t being closely managed and yields on local securities

are not negative when adjusted to inflation. Appetite remains

weak, going by a gauge of demand for Egypt’s 12-month

securities.

A much larger reliance on bond sales will ring alarm bells,

indicating Egypt is rowing back on plans to wean itself off hot

money and returning to an approach that helped spur the current

crisis.

Gulf Aid

Expectations that Egypt’s Gulf allies would fully open the

taps have been misplaced. Almost a year since more than $10

billion of investment was pledged, only a fraction of this

funding the IMF has called critical has materialized. Saudi

Arabia’s recent comments about seeking reforms before it

supports other nations sparked speculation over the holdup.

All this means the next large-scale deal — mostly likely

involving the sale of an Egyptian state-held stake of a major

company to the United Arab Emirates, Qatar or Saudi — may be a

watershed moment, swiftly followed by more transactions. It may

signal Gulf investors see the pound as having bottomed out,

finally allowing them to settle on what they see as fair local

prices for assets.

State Exit

Deep in the IMF’s latest report were lines that may be key

to Egypt’s future: a promise that overarching state involvement

in the economy, including by the army, will be curbed. It

tackles head-on a long-standing complaint that the private

sector has been crowded out, discouraging badly needed foreign

investment.

Read More: Egypt Puts State Assets Up for Sale to Hunt

Foreign Exchange (2)

No one’s pretending it’ll be easy. The IMF, which also won

a pledge that state entities will regularly open their accounts

to the Finance Ministry, has warned any re-balance “may face

resistance from vested interests.” Egypt has named 32 state-

owned assets in which it’s selling stakes, and swift movement on

the offerings would be taken as a positive step. Also key will

be the long-mooted first-ever sale of an Egyptian army-linked

firm — that of Wataniya, a fuel distributor running a vast

national network of gas stations.

Inflation

Galloping inflation that’s showing no sign of easing is

heaping misery on Egypt’s more than 100 million people, working

and middle classes alike. Food prices soared in January at the

fastest pace on record, and the government says tackling the

surge is a top priority. Families are cutting back and Ramadan-

period state discounts have been introduced early. The state

nutrition watchdog’s suggestion that Egyptians eat more chicken

feet spurred anger.

Authorities are mindful of the risks; increasing costs of

living helped trigger the Arab Spring uprisings a little over a

decade ago. When inflation begins to slow — possibly in the

second half of 2023 at the earliest – that might give some

modest comfort.

–With assistance from Farah Elbahrawy and Netty Ismail.

To contact the reporter on this story:

Mirette Magdy in Cairo at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Sylvia Westall at [email protected]

Paul Abelsky, Michael Gunn