By Ugur Yilmaz and Asli Kandemir

(Bloomberg) — If you’re looking to buy a lot of dollars in the Turkish market, expect to explain yourself. The Turkish central bank has so tightened its grip over the foreign-exchange market in the runup to May’s presidential election that it’s become the matchmaker for most large transactions, according to several traders who spoke on condition of anonymity. Nearly every trade larger than a few million dollars is subject to its scrutiny and approval, they

The traders describe a central bank that’s constantly on the phone with banks, that tracks and vets prices as soon as bids appear on trading platforms, and demands detailed reports on currency operations. In essence, matchmakers from the central bank are largely determining who sells to whom and at what rate,

The central bank declined to comment.

Such oversight amounts to “mild forms of capital control” that are unlikely to be sustainable far past the elections, according to Ulrich Leuchtmann, Commerzbank AG’s head of currency strategy in Frankfurt.

“It seems logical to assume that Turkish authorities will try to maintain the status quo, i.e. only moderate depreciation speed, until the elections are over,” he said. But “no central bank can permanently fix the exchange rate of its currency at non-sustainable levels” and “in the end, either Turkey’s capital account has to get more closed or they will have to accept lira depreciation at a faster pace.”

Deploying a new phone-based matching service, the central bank’s officials have been calling banks daily to pair corporate demand for foreign currencies with supply. That’s amounted to an

effective ban on foreign-exchange purchases without approval from the central bank, which requires “valid” reasons for buying and allows it only if there’s a matching flow of dollars into the market.

The current spate of interventions differs from those of the past in scale, frequency and scope, the traders said. Previously, authorities were trying to control foreign-exchange supply, but now they’re also controlling demand.

With transactions tightly managed from Ankara, signs of stress have started to emerge in corners of the market, including occasional spikes in the dollar-lira pair during early or late trading hours, and massive temporary jumps in lira borrowing costs overseas. The Turkish lira fell by 0.9% to 19.29 against the US dollar in early trades on Wednesday, before returning to its steady course.

The government has sought to contain such fluctuations with further interventions, including requiring lenders to sell dollars to some customers at a premium to the market rate. Scores of other regulations have been introduced to support what the central bank calls “effective functioning of financial markets.” And some transactions have been re-directed to the futures market to prevent pressure on the spot rate. The steady Turkish currency has caused problems for exporters who claimed to be struggling to compete with a stronger lira. The central bank introduced an initiative in January to offer a more favorable exchange rate to exporters who commit not to purchase foreign currency later. At the same time, demand for cash dollars has increased, leading to a premium on the greenback in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar gold market and resulting in varying exchange rates for the lira.

Steep Cost

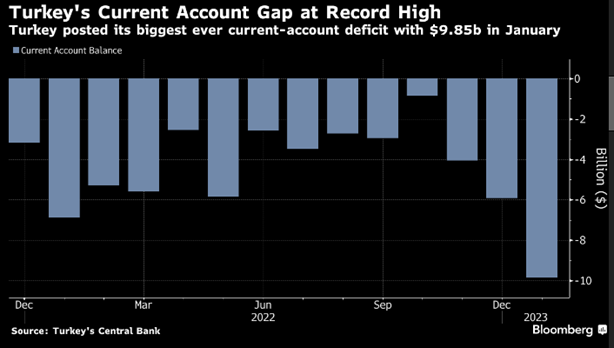

The central bank’s intervention comes at a price. Bloomberg Economics estimates the back-door currency-market operations have cost about $128 billion since December 2021. The bank’s net foreign-exchange position is negative when liabilities are accounted for, and Turkey’s current-account deficit surged to $9.85 billion in January, the steepest on record.

Turkey abolished a crawling-peg currency regime and moved to a floating rate in 2001, just before a major financial crisis. Lira traders and central bank officials have occasionally clashed over the new policy, which many now liken to a “managed float.” The spread between the lira’s three-month and one-month implied volatility shows investors are betting it won’t last much beyond the vote, regardless of who wins.

“Given that FX interventions are very costly, the central bank may eventually allow the lira to trade far more freely after the elections,” said Piotr Matys, a senior currency analyst at In Touch Capital Markets in London.

To contact the reporters on this story: Ugur Yilmaz in Istanbul at [email protected];

Asli Kandemir in Istanbul at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Harvey at [email protected]

John Viljoen